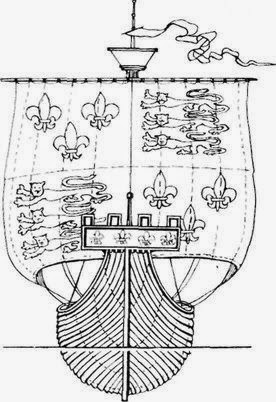

A ship from Richard III's

reign.

In the absence of royal initiative in England,

however, there were others who were willing and able to wield the

strength derived from a force of ships to intervene in the

increasingly complex struggles between competing factions and

claimants to the throne. This is most clearly seen in the case of

the Earl of Warwick, but the Duke of Burgundy and the king of

France were also prepared to provide naval forces to support their

favoured candidate for the English throne. Richard Neville, Earl of

Warwick had been captain of Calais since 1456 and had taken the

opportunity afforded by a relatively secure base to build up a

squadron of ships. These were used in the manner most likely to

advance the fortunes of the Earl himself and the Yorkist cause,

which, at that time, he supported. To many English men his naval

exploits in the Channel were a welcome sign of 'enterprise upon the

see'. Jack Cade's proclamation in 1450 at the outset of the Kentish

rebellion had bewailed the facts that, 'the sea is lost, France is

lost'. The French raid on Sandwich in August 1457 had been a

humiliating reminder of the impotence of English defence. Now John

Bale, himself a merchant and a ship-owner, could laud Warwick in

his chronicle, praising his 'greet pollecy and dedes doyng of

worship in fortefieng of Cales and other feates of armes'. To

modern writers Warwick's deeds seem at least semi-piratical but to

his contemporaries his attack on a Spanish squadron of 28 sail off

Calais in early June 1458 and his taking of around 17 prizes out of

the Hanse fleet returning with Bay salt later the same summer were

victories to savour. It even seems not to have affected his

reputation that the first engagement was not entirely successful.

John Jernyngham's letter to Margaret Paston which gives details of

the encounter, recounts how he and his crew boarded a large Spanish

ship but were unable to hold her. He concludes, 'and for sooth we

were well and truly beat'. The point to contemporaries was that

Warwick, who was in fact bound by an indenture of November 1457 to

keep the seas, seemed to be acting energetically and speedily even

if not all his opponents were clearly 'the londes adversaries'.

His activities in 1459 and 1460 demonstrate

with greater force the way in which the possession of a squadron of

ships with experienced crews was greatly to the political advantage

of both Warwick personally and the Yorkist cause. After plundering

Spanish and Genoese shipping in the Straits in the summer of 1459,

Warwick, who had joined the Yorkists in England, seemed to have

miscalculated when he was forced to flee from the battle of Ludford

Bridge. He reached his base in Calais safely, however, and from

that point acted with great skill. Lord Rivers and Sir Gervase

Clifton for the king had by December managed to impound Warwick's

ships in Sandwich harbour. The Crown also mustered a small force

under William Scott to patrol off Winchelsea to repel any attack by

Warwick. Warwick had many friends in the Southern counties, perhaps

beneficiaries of his earlier actions in the Channel. Through them

he was well aware of the Crown's plans. In January a force from

Calais commanded by John Dinham, slipped into Sandwich early in the

morning, while Rivers was still abed, and persuaded Warwick's

erstwhile shipmasters and crews to return with them to Calais. The

royal government attempted to counter this loss by commissioning

further forces to serve at sea against Warwick. The Duke of Exeter

in May 1460 in fact encountered Warwick's fleet at some point to

the east of Dartmouth and arguably had the opportunity at least to

damage very severely the Yorkist cause if not put paid to it

entirely. Yet as the Great Chronicle of London put it 'they fowght

not'. Richmond sees this as 'one of those critical moments when

action was essential but was not forthcoming'. In his view Warwick

had what the Crown did not, a fleet and a fleet which was used to

keep the sea. The use of that fleet was an important factor in the

course taken by the domestic politics of England and to Richmond

sealed the fate of the Lancastrians.

In 1470, Warwick was personally in a much

weaker position. He may still have had some vessels of his own; on

his flight from England, after the failure of his intrigues on

behalf of the Duke of Clarence, pursued by Lord Howard, he had

taken prizes from the Burgundians. He could not, however from his

own resources hope to mount an invasion of England to restore his

new master Henry VI. He and Queen Margaret were dependent on the

aid of Louis XI of France to provide such a fleet. This aid was

forthcoming because of the seeming advantage to France in the

restoration of the Lancastrians and their adherence to an alliance

against Burgundy. Both English and Burgundian naval forces,

however, were at sea all summer in an endeavour to keep Warwick's

French fleet in port. Their efforts seemed successful; by August

Warwick's men were demanding their pay and the people of Barfleur

and Valognes had had enough of their presence. A summer gale then

dispersed the Yorkist ships at sea and Warwick sailed across

unopposed landing on 9 September near Exeter. By the end of the

month Edward IV was himself a fugitive restlessly watching the

North Sea from his refuge at Bruges with Louis de Gruthuyse, the

Burgundian governor of Holland. If he in his turn was to regain his

throne his need also was for ships. The Duke of Burgundy was

perhaps more discreet in his support for his brother-in-law than

Louis XI had been for his cousin, Margaret of Anjou. In March 1471,

however, Edward left Flushing with 36 ships and about 2000 men and

once ashore at Ravenspur by guile and good luck recovered his

Crown.

In the 20 or so years from 1455, therefore, it

can be argued that the possession of the potential for naval

warfare could be of great advantage to those who wished to be major

players in both internal and external politics. No very great or

glorious encounters between the vessels of rival powers took place

in the Channel or the North Sea. The typical action was that of the

commerce raider; a brief violent boarding action ending probably in

the surrender of the weaker crew in an attempt to save their skins.

Kings and other rulers possessed very few or no ships of their own

and were reliant on the general resources of the maritime

community. Yet, despite this, the perception of the pressure, which

could be exerted by a fleet in being, was more widely appreciated.

Warwick has been held up as the individual whose actions

demonstrate this most clearly and it is hard to argue against this

opinion. He, perhaps, until the fatal moment on the field at the

battle of Barnet, also had luck. Would he have fared well if Exeter

had attacked off Dartmouth in 1460? The reasons for Exeter's loss

of nerve are not really clear. Exeter had many warships including

the Grace Dieu, built by John Tavener of Hull and formerly

Warwick's own flagship. The Great Chronicle of London speaks

vaguely of Exeter's crews being unwilling to oppose Warwick while

the English Chronicle states baldly that Exeter was afraid to

fight. Waurin, a Burgundian chronicler, has a circumstantial

account of Warwick approaching the coming conflict with great

circumspection, sending out fast small vessels ahead of the main

fleet to gather intelligence and then calling a council of war of

all his ship masters.47 The decision was taken to attack with

vigour and maybe the sight of Warwick's ships coming on at speed

with the advantage of the wind terrified Exeter. His lack of

courage was certainly a disastrous blow for his party.

On a wider canvas, the situation in these

waters as far as the relations between rulers goes has become much

more open. In the first third of the century the conflict between

England and France was the dominant factor with other states being

drawn in as allies of one or the other combatant. After the middle

of the century states pursued their own commercial and political

interests in a more fluid situation. Naval power was diffuse, not

necessarily concentrated in government hands, and the advantage

might swing quickly from one state or group of traders to

another.

No comments:

Post a Comment